|

The Bard of Brittany

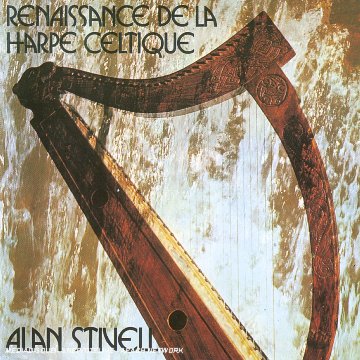

1971, that's when this amazing album appeared, 1971...that was long before the rising of the many Celtic bands

that now dot the musical landscape. Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique was and is a revelation. First off it's entirely instrumental,

secondly it's an album that doesn't come from Scotland, Ireland or Wales, the usual suspects, as it were, no, this album was

from Britany. The Breton, they who fled in the face of the Anglo-Saxon invasions, they who are linguistically closer to The

Cornish than they are to the Welsh, the Irish, or the Scots. They've been killed, in the past, for daring to speak their

native tongue, as, of course have many Celts and Gaels. The music was all but gone, except in a few isolated pockets. Some

of the songs had been committed to paper, but they were held by the scholars and treated as 'interesting artifacts' to be

poured over and analysed to death. Then...then along came Jord Cochevelou, a civil servant in the French Ministry of Finance.

His dream was to recreate a Breton Celtic harp. After studying ancient documents, he reconstituted the long-forgotten

instrument, and gave the first prototype to his nine-year-old son Alan in 1953. Alan, in later years, would become known to

the world as Alan Stivell.

Alan Stivell, whose real name is Alan Cochevelou, was born on January 6 1944 at Riom, Auvergne,

France. His family, whose birthplace was Morbihan in Brittany, moved to Paris shortly afterwards.

Alan learned the classical harp and the piano. He began classes with Denise Megevand in May 1953, helped by his father. He performed for the first time in November, before an audience at the Maison de la Bretagne,

Paris, during a press conference held by his professor to show the newly created celtic harp. In 1955, he played 3 pieces

in the introduction to the Line Renaud show at the Olympia in Paris.

In 1957, young Alan began seriously learning the Breton language. He also studied celtic history, mythology

and art, thus linking up with his ancestry. He also began playing the bombarde and the Breton bagpipes, both much used

in traditional Breton music. He then joined the Bagad Bleimor folk group, where he was the lead.

His first recording experience was in 1959, when he recorded a single. It was the following year, in fact,

that his first real album came out. "Telenn Geltiek" was devoted to celtic harp music.

His father built him another harp in 1964, a bardic one with bronze strings. Alan decided to launch into

a new adventure, experimenting with modern music. In 1966, he started singing, performing in many clubs, festivals and Youth

clubs (Maisons des Jeunes et de la Culture).

Two years later, he sang the opening part of the Moody Blues concert in London. It was in 1970, however,

that the career of the singer now known as Alan Stivell began. His single, "Broceliande" came out in July under the Philips

label, followed by a later album, "Reflets", and were his first hits. In the vanguard of the folk revival, Alan Stivell offered

a version of Breton music which was resolutely modern and of the future, thus attracting a young public seeking assurance

of their regional identity, while not becoming entrapped by it.

In 1971, Stivell brought out an album entitled "Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique", which was only instrumental,

containing traditional melodies based on cords and voice, with some bombarde, percussion, even guitar accompaniment

by Dan Ar Braz. In 1972, he was acclaimed at his concert at the Olympia in Paris. With him were musicians such as Dan Ar Braz on electric

guitar, Gabriel Yacoub (later known as Malicorne), and Michel Santangeli, a rock drummer. The live album recorded at this

performance sold nearly one and a half million copies. Alan Stivell's growing success led purists to accuse him of making

music just for the sales. It was the final flash point, the world new of the true depth of Celtic music and from that point

on never looked back.

the musicians on

Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique

Alan Stivell

chant, harpes, cornemuses

Dan Ar Bras

guitare

Michel Delaporte

percussions

Guy Cascales

batterie

Gérard Levasseur,

Gérard Salkowsky guitare

Gilles Tinayre

orgue

Yann-Fanch Ar

Merdy batterie ecossaise

Mig Ar Biz, Alan

Kloatr bombarde

Jean Huchot, Henri

Delagarde,

Manuel Recassens

violoncelle

Stéphane Wiener,

Gabriel Beauvais, Paul Hadjaje,

Pierre Cheval

alto

Jean-Marc Dollez

contrebasse

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Philips 6414406 1971 |

|

|

Ys

Marv Pontkalleg

Ap huw

Ap Huw and Penllyn

Eliz iza

Gaeltacht

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

related internet links

|

|

festival of music, dance

& history from Wales,

Scotland, Cornwall, Isle of Man,

Galicia, Brittany, Ireland and

Asturias

the texts on this website covers

much of the early time frame that

we'll be looking at here.

the mythology of Celtic polytheism,

the apparent religion of the

Iron Age Celts. Like other Iron Age

Europeans, the early Celts

maintained a polytheistic

mythology and

religious structure

Scotland's Online Resource Centre

for Celtic Studies, plus information

about instruments, Celtic customs

Welsh Celtic Rock Band

no fiddle, no pipes, no concertinas

but Celtic to the bone

Kuzul Etrevroadel Evit Kendalc'h

Ar Brezhoneg

established in 1975 in Brussels,

Belgium, to support the repeated

demands of Bretons that their

native language be given the

recognition and place in

the schools, media and

public life of Brittany

that it needs to survive

a collection of information on the

instruments and playing styles of

traditional Scottish and Irish music.

This is not intended to be a

complete listing of all instruments

in current use. For that, try Ceolas.

an overview of the

telenn or Breton harp.

Although most folks think

of Celtic music, in their mind

they hear Irish or Scottish music.

However.....

all things traditional

plentiful coverage of

the Celtic and Gaelic scene

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|